exhibitions at baumgarnter with dreams

some of these dreams: click

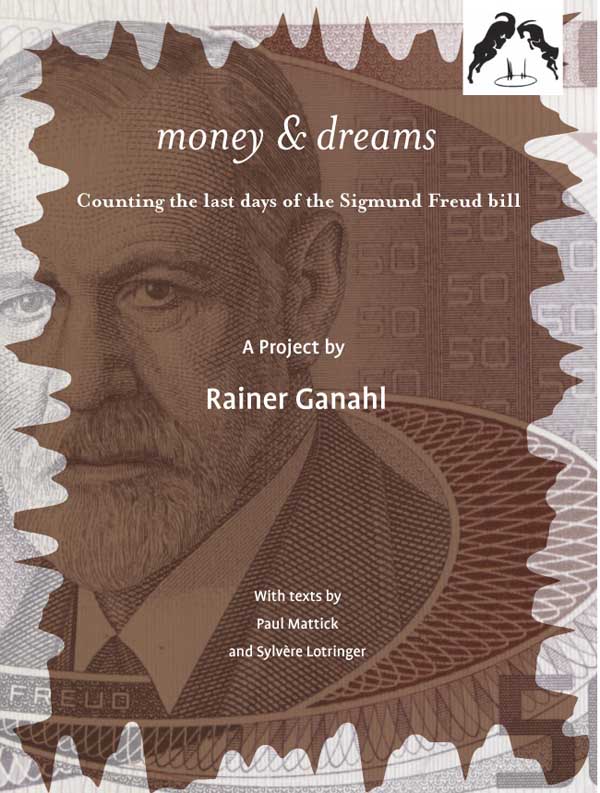

text is below : forthcoming March/April 2005 (goes in print in January) (spring publications)

Who wants to know anyway? --- (last corretion)12/17/04

Dreams are easy to forget. But the stuff dreams are made of is not. I started to record my dreams in the summer of 2001 after I saw a 50 Austrian Schilling (ATS) bill on a refrigerator at a party in Brooklyn. I was wondering about the decorative functions of Austrian money in the USA. I was told Sigmund Freud is depicted on it. This was a surprise to me, who had used this money for so many years without being aware of it. I soon learned that many fellow Austrians ignored this little fact as well. I found it peculiar and indicative of Freud’s writing itself. With the looming introduction of the new European currency, Austrian legal tender was doomed to disappear. During the remaining eight months that Freud’s paper image circulated in the hands, pockets, cash registries and banks of Austrians, I created this dream-farming artwork, which I entitled Das Zählen der letzten Tage der Sigmund Freud Banknote, translated as The counting of the last days of the Sigmund Freud money.

For this work I tried to remember my dreams and write them down as quickly and accurately as I could, often at the “scene of the crime,” that is, in bed, sometimes shaken up by a nightmare. Since I am not trained in figurative depiction, my dream notation was mostly done with word, only sometimes accompanied by clumsy drawings. With the help of this scribbling I was later able to carry some of the dream memory into the morning and transcribe it more legibly onto the computer. I realized soon that this “immediate writing down in bed” was essential to recollection since dreams are so fragile that even a change of my physical position could liquidate memory. Rereading my loose handwriting of single words and sentence fragments is, even for me, not easy since it often was done in the dark in the middle of the night. Dreams with more dramatic texture usually wake me up easily. The oneiric scenes could be so intense and colorful that my initial appeared often falsely accurate. With the partial or entire loss of dream content, at least, these meager reminders were helping me to remember or reconstruct a dream for more detailed explication on the computer. Our unconscious mind works with all kind of tricks to secure deceptions and dream evaporation. For example: I would dream I was writing down a dream and continue to sleep, only to discover later in the morning that I’ d written nothing down at all. So-called “lucid dreams,” in which I dream-watched myself became frequent and I felt released when this dreaming marathon stopped and I could let all my dreams just pass by again unnoticed.

After having written down the dream on the computer, I checked the value

of the 50 ATS bill on CNN’s online currency converter. Simultaneously,

this online service gave conversions for a number of other currencies.

I complemented these listings with the economic data of two major US stock

indexes, the Dow Jones and the Nasdaq. At that moment, I also checked

how many books on Sigmund Freud were offered on Amazon.com and on Buecher.de,

a German equivalent to the US online bookseller. After printing a dream

with all the information on the same paper that contained the original

dream scribbles, I added the 50 ATS bill with Sigmund Freud’s face

on it. The production of these artworks was contingent on my dream activity,

that is, no dreams—no works. In the period from July 1st to the end

of February when the actual currency ceased circulation, I produced 144

works with dreams. Thought mostly I slept at night, sometimes I also fell

asleep during the day and dreamt. Many works contain multiple dreams,

since I quite often dream several times a night. I experienced myself

as a serial dreamer.

This dream work had quite an effect on me. Before I started with it I

went dream by dream and didn’t pay much attention to my dreaming.

I was not aware – to give an example – of how often I was dreaming

of my native Austria where I haven’t lived since 1986, and of Vorarlberg,

the region I grew up in, which I left behind in 1980. The amount of Vorarlbergian

or Austrian dream background has been a real surprise to me, something

I only became conscious of when working through these dreams. Even more

intriguing is the fact that right now, years after I completed this work,

I now see it in a different light. At the time of dream harvesting, I

had limited understanding of how my former personal relationships influenced

me. A five-year-long relationship had come to an end and I fell in love

with a new girlfriend, who featured quite prominently in my dreams during

the eight months of dream registering. Even though I dreamt of my ex-girlfriend

from time to time, I was not aware of her oneiric appearances during that

period of dream accounting. Rereading my dreams is quite an adventure

evoking embarrassment and surprise since I have forgotten most of the

dreams.

Apart from my personal and professional live, my family history and all

the dream-gossip reflecting socializing and stress, people and personal

drama, there is also an important historical tragedy of catastrophic consequences

that entered this work. The duration of this project overlapped with the

events of September 11, 2001, the subsequent lethal anthrax letters and

other threats. These dramatic events did direct some of my dream production,

mixing up news and paranoia, post-trauma symptoms and existential nervousness.

In these dream scenarios I featured in nearly all possible roles: as victim

of terrorism, as terrorist, as CIA agent, as victim of anti-terror campaigns

and so on. Terrorism and the overblown wars and campaigns to counter terrorism

resulted in gruesome and sickening images paraded on TV that created unconscious

and subtle effects also live at night. Thus, the psychic collateral damage

of 9/11 and the subsequent War on Terror were leaving traces in much of

the oneiric quilt I left behind. Dreams resist final interpretation but

they are open to contextualization. They also invite associations and

new narratives resulting from the dream content remembered. In this work,

I never tried to “interpret” it in a classical sense. I didn’t

want to “play Freud,” but supplemented many dreams with accounts

on the dream context. This process of contextualization never ends due

to the nature of language and the endless turns our lives are always taking.

The difference between actual dream narratives and contextualizations

is not always clearly understood by readers. For this work my dreams are

not indicated as dreams and clearly distinguished from contextual complements

and associations. I opted for the fluidity between these different layers

of texts to prevent readers from clearly pinpointing a story, a fact or

a person. This helps to create a vaguely inconsistent narrative that constructs

a space where a writing subject passing as “me” emerges just

to disappear again into some extra-layers of stories.

Everybody can relate to dreams since dreaming is universally human. I

myself see my contextualizing explanations and dream associations as just

a first reading, compressing and decompressing stories, thus sending subsequent

readers in various directions. To a certain degree, any account, including

court papers or visually recorded facts, is fictional and gain reality

only through context, through authority and through the various laws that

govern the construction of our daily world as facts and reality. Recent

American politics provide good examples of how facts – the War with

Iraq, terrorism, redistribution of wealth to the wealthy, a failing economy,

the criminal behavior of a president and his administration, etc. –

seem not to matter, in fact seem to be up for endless spinning and political

power games. In our society, usually, dreams no longer play any real part

in the construction of reality – unless one is in the well-paying

business of psychoanalysis. I can “have a dream” of justice,

a dream of being rich, of being here or there, but all these dreams don’t

simply create any actuality after awakening. Or do they in the minds of

people?

When it comes to corporate dreams the situation of constructing reality becomes a different ball game. Hollywood and companies like Dreamworks fabricate digital and celluloid dreams en masse that shape reality to a degree that renders surreal reality real, as we saw in the last Californian election. The dreams of Arnold Schwarzenegger – the most know Austrian after Hitler and Sigmund Freud – have come true. Most marketers try to sell us pre-fabricated dream products of all sorts, using dreaming as a seductive sales pitch. What these political, business and advertisement schemes operating with words and visual ideas of dreams don’t mention is the fact that many of our dreams are actually nightmares – something that readers of my dreams will quickly be aware.

Sigmund Freud himself sees in any regular dream an aspect of a Wunschtraum,

that is, wishful dreaming, or wish fulfillment that is falsely translated

by my online dictionary as “pipe dream” or “great dream.”

This element of desire for material, social, ideological, psychological

and erotic realities in “great dreams” and less great ones reinforces

the intrinsic relationship between dreams and a truth that seem to be

suspended. Dreams fulfill in a very individual, spontaneous and unmediated

way the same reflective functions as utopias do in the realms of political

and ideological screening. In today’s world of massively unfair and

incredibly unequal distribution of resources, dreams - cashed in or not

- serve as colorful liquid pumped through all political, economical and

social systems globally. Thus, individual and global dream worlds can

be studied in the same way oncologists use traceable fluids to detect

cancerous cells.

Martin Luther King had a dream for which he had to pay with his life.

Dreams not only can be a threat to others but can also be quite repulsive

to our own psyche. The explosive amalgam of truth, desire and anti-gravitational

immateriality needs various mechanisms to be kept under control. This

is why many dreams go uncollected, unremembered, untold or become self-censored.

Self-censorship starts with the personal inability to remember stuff in

the first place, if one accepts the commonly accepted ideas of our personal

conscious/unconscious information economy. In my dream reporting, self-censorship

also plays a conscious role, though I tried to be as honest as possible.

But I do remember some instances of balancing the consequences of disclosing

certain details about others and myself against an implicit drive for

authenticity and artistic responsibility for truth. In a couple of alienating

dreams with embarrassing or too painful contextualizing associations I

opted for wandering vagueness and blurring oblivion. In some instances

I also switched between languages something that usually wasn’t related

to self-censorship. The question of (self-) censoring also plays a role

in selecting the material to be printed in this volume since we can afford

to reproduce only 100 works. I therefore delegated this selection primarily

to the editor of this series in order not to self-censor myself.

An ineffective, naive way of dealing with this issue of self-censorship

is similar to the tactics of children who close their eyes and believe

that they are not visible anymore. As I write this text I sense a refusal

on my part to re-read my collected material. It is as if I don’t

want to regain yet another view on the state of these eight months of

oneiric self-observation. I hesitate to be reminded of these dreams. I

am reluctant to see what was going on in my life at the time of dream

recording. I vacillate to see two life-defining love stories blend into

each other and diverge. It is painful to see love and oneself change and

time pass. It is unheimlich to suddenly recognize conflicts of the current

relationship already inscribed in the very euphoria of early love where

problems seemed simply not visible. Also, the events and after-events

of 9/11created a schism that did away with a political innocence, a situation

nobody really wanted to anticipate. Today, we really don’t want to

remember 911 or even project yet another attack of even larger magnitude

and destruction. Hollywood and politicians whose lifeblood is fear are

insinuating threat scenarios for us. In analogy to Sigmund Freud’s

death drive, one could wonder whether it makes sense to speak of a drive

to forget, a drive of oblivion and ignorance. Who wants to know anyway?

Friedrich Nietzsche was one of the fiercest advocates of oblivion and

wanted to make it a human virtue. In political and public life, the power

to forget – and to keep others forcefully from remembering –

as well as the power to ignore are vital instruments to staying in power

or grabbing power. Personal heuristics fortunately/unfortunately follows

the same path. We don’t want to remember loss and painful things.

I hope that very few people will actually read these small and often badly

written writings. Finally, readers will read it their way, mix in their

own memories, their own dreams and lives and my stories will hopefully

defuse.

Indeed, the actual quality of the writing is peculiar to say the least. There are plenty of orthographical, lexical and grammatical mistakes, which have not been edited out. For multiple reasons, some of which are addressed throughout this introduction, I prefer not to reread either my emails, or many of these dream texts. This “write and run” style sometimes approaches incomprehensiveness and marks an “anything goes” attitude that may also be explained by the fact that I’m not a native-speaker and depend on editors. This doesn’t apply only to English but also to German, my so-called mother tongue, though my mother spoke Vorarlbergian dialect, which is not written officially and which is in many ways quite distant from standard German. To address this subject more accurately, I only remember the Vorarlbergian voice of my father and not that of my mother. My mother passed away in a violent vertical way of her own choice when I was fourteen. To this day, I have no acoustic memory of her. I cannot remember her voice and don’t recall a single sentence, a single word she uttered. For me, dealing with proper grammar and correct spelling in my “teachers’ tongues” feels authoritarian and rule governed. I also found out that if I ignore orthographical rules consistently enough, I might get away with it.

Getting away with things had always played a crucial role in my life,

since I had many issues to escape from. I like to name my practice of

learning many foreign languages – currently Chinese and Arabic –

as a “moving away from my mother’s tongue.” Many of my

dreams were mediated, caught and objectified in German, English or in

some other language – depending mostly on the dream context. We know

that dreams may occur even in languages or with words that don’t

exist. More or less evenly I wrote out dreams in English and in German

and was never really aware of why this or that language offered itself

for use. It just occurred. I also often switched linguistic codes and

mixed them up sometimes even within a single sentence. This most likely

is a product of the fact that I have been living outside a

German-speaking country since 1986. In New York, my use of German is limited.

I don’t evade German as did Louis Wolfson with his mother tongue.

This great New York writer learned many languages in order to refuse to

speak English, his mother tongue. As opposed to me, he is very eloquent

about the voice of his mother, which he hated. He wrote the telling fabulous

two books called “Ma mère musicienne est morte” (My mother

musician is dead) and “Le schizo et les langues.” (The schizo

and languages)

Recording my dreams was like interviewing myself with little interference.

As in good interviews, for this “neuro-matic” viewing no questions

were necessary. Questioning the narratives of dreams is little desirable

since desires rule our libidinal empire of dreams. The answers are of

a similar material: obsessive exaggerations and possessive distortions,

paranoid constellations of freeze framing and threat, the ever returning,

all too natural drive for sexual ludism and seduction as well as delirious

and twisted social interplay and intrigue. The word “interviewing”

is very accurate for dreaming, which delivers mostly images of our cathexes,

our mental energy directed towards a particular idea or object.

Money is one of the most prominent cathected objects there is. This is interesting in that money is in and of itself worthless and has value only when exchange is possible. Exchange doesn’t need to be effective but needs to be optional. The day, after I finished this dream work, nobody --– except the Austrian National Bank – would accept the Austrian Schilling as legal tender since this role had been passed onto the Euro. According to Talcott Parsons and Nicolas Luhmann, money is a symbolically generalized medium of value and exchange and shares this quality with other media. I am now interested to project money onto dreams and ignore for a while the usual way money and dreams are associated together when we “dream of money.” Not only money is a medium, so are dreams. Since ancient times, dreams were interpreted and were looked as messengers of the gods. Before Freud institutionalized psychoanalysis and made out of dreaming a cottage industry, dreams already communicated the wishes of god, the state of our minds and were considered informative for the health of people and communities. Money enlarges the possibilities of exchange and frees transactions from temporal, material and social constraints. Dreams worlds, too, are unlimited in their actions and timing and cross social, economic, ideological and sexual boundaries frequently. If capitalism can be reductively paraphrased as making money with other people’s money, work and time, dreams too make use of the full scope of imaginable and unimaginable instruments, protagonists, actions, interactions and settings.

The very structure of money is based on scarcity. In cases where money is easily accessible to everybody without consequences there is not much to be exchanged, as was the case in the former communist countries. In other precarious situations where plenty of money is in circulation, the currency is worth little and inflation can render it less relevant. In such circumstances, significant exchange resumes without paper money of that given currency. Scarcity of money is therefore an intrinsic element for the proper functioning of money, which brings to my mind the omnipresent structure of dreams as Wunschtraum, the dream in which we desire and want something. Money and dreams are therefore perfect bed fellows in our wishing system. The discrepancy between reality and dreams concerning the allocation of wealth, love, time, space, justice, power and everything else is most likely one of the driving force in oneiric ambitions. Mocking the world of material differences, one might ask, “What’s the point of dreaming if you have got it already?” It is difference that powers our dreams and the world in which we dream.

Money as a generalized medium of communication has the powerful capacity

to establish relationships between diverse and non-comparable things.

Money is therefore a unifying element of difference without eliminating

or excluding differences. The most unrelated and incompatible facts, situations,

objects and people may converge into relationships with the help of monetary

instruments or the pure imagination of them. This became very apparent

in the insurance files of the World Trade Center disaster, also a major

stage in my dreams, which tagged prices not only onto lost and destroyed

property but also onto lives and future lives of the people who were killed.

This integral function of money with its high degree of generalization

finds its equivalent again in dreams, which also ignore facts, times,

geographies, borders, habits, social orders and politics. Anyone could

indulge in delirious dreams about Princess Diana though she is not anymore

among the living and is inaccessible. Dreams are made of decoy materials

that render libidinal energies and vibrations promiscuous and versatile.

We often see alliances in dreams that would be impossible but desirable

or are abject and unthinkable in real life. Dreams flow in liquids that

are as lubricated as money.

Actual money – cash or more to the point: cash flow – is already

anachronistic and will soon not only be irrelevant in business but also

more likely even prohibited for tax and “security” reasons.

Money is about to be stripped naked of all materiality and will become

pure information and fully transparent. In the near future, we will stop

using money and checks and only deal with wire transfers and bank and

debit cards of all kinds. Already, it is impossible to purchase airplane

tickets without a credit card, and nearly impossible to make phone calls

in Europe without a plastic card. More and more machines want to be fed

with machine codes and electronic ID chips only. These monetary interfaces

are about to learn to communicate without any visual or physical contact

to a scanner. I wonder whether this explosion in environmental interactive

intelligence, in which pecuniary transactions and information play vital

roles, won’t soon turn into nightmares. From a subjective point of

view, wiring money or debiting a purchase with plastic may feel like having

the limbic regions of the brain, responsible for emotional and emotive

matters, communicate with the prefrontal cortex that houses our working

memory, our attention unit, and our logic and self-monitoring center –

all functions that are suspended during the dream-enriched time of REM

sleep with Rapid Eyes Movements.

For Nicolas Luhmann, money is at the center of an economic theory that

is dominated by “improbable communication” which has as its

binary code payment and non-payment. The economy is therefore seen as

the totality of all contingent necessary and non-necessary, executed and

non-executed payments. The problem of money is an integral part in this

game of probabilities which determines the acceptance or refusal of economical

communication, that is, payment or non-payment. The experience of contingency,

the choice to buy or not to buy, to pay or not to pay, to sign on or not,

regulates not only prices but also implies a high degree of (market) observation

and self-observation. It was therefore not arbitrary that I added the

value of the money at issue and other key economic factors. In the world

of anti-gravitational dreaming, probability is not a non-issue. We still

dream that we want to escape the monster or killer and are petrified and

unable to escape. Last summer in East Hampton, a telling nightmare was

reported by a six-year-old daughter of one of my few wealthy friends.

The little girl awoke from a dream in which her parents lost all their

money in exchange for poverty. Her unfortunate dream might have been inspired

by my fascination for such a fabulous villa or by the fact that on that

famous peninsula, not a single stone goes without a big exuberant price

tag. In East Hampton, people don’t “own houses,” they are

“in the market.” Wish fulfillment is disguised in such a case

dialectically through the fear of loss. The dream-come-true vacation situation

creates new nightmares when one is confronted with people living realities

in which non-payment options are the dominant ones.

Of course, economic transactions are observed and consumed even by people

who are excluded from direct participation. Luhmann even paraphrases Marcel

Duchamps’s famous grave inscription that reads “D’ailleurs,

ce sont toujours les autres qui meurent…” (But it is always

others who die). He says, “Die Wirtschaft – das sind immer die

anderen” (The economy – is always made by others). This market

transparency is important for the market to function. Others therefore

join and participate even though they might not be able to enter the payment/non-payment

game. Price structures and the quantity of economic transactions help

us to orient and position ourselves in this sea of possible payments and

non-payments. Presenting my dreams to a public constitutes for me some

kind of an embarrassment that I try to hide through this abstract introduction

and my quasi-refusal to even re-read my own dreams. As I mentioned earlier,

because they are products of my lived background and existential patterns,

these dreaming recordings are communicating residues of the primal pleasure

and pain, the original comfort and stress that this stuff is made of.

Live goes on and we don’t always want to know about it. I refuse

to be fully aware of exactly how much intimate and personal detail I disclose

about myself, my family and my social circle. I’m also concerned

that these dream writings and post-oneiric associations could hurt the

feelings of others, addressed in this work, something that will create

a new layer of conflicts. Luhmann, like Parsons, could be accused of paying

relative little attention to conflicts, crisis and all those social situations

where the euphemisms of a unifying system theory appears out of sync with

non-anticipated ruptures of rule-governed behaviors and wars. In my dreams

as well as in life, conflicts are everywhere and I wonder whether I am

just an artist or a nocturnal worrier. Today, the optics of dream literature

is well domesticated and room is provided to accommodate the colorful

expressions of “primitive, sexual and aggressive impulses” –

as academic books sometimes put it. Dreamers, writers and artists thus

get some bourgeois apologetic nimbus to function as pathetic, neurotic,

paranoid and enlightened informer on contemporary society. Without being

limited to dreaming, these figures are even expected to create bizarre

imagery, suspend current logic, create distractions, and morp times, places,

identities and histories.

Not because of this Narrenfreiheit, the jester’s license, I finally

want to point out that the vanished Sigmund Freud on the Austrian money

was also a reminder of the fact that not too many decades earlier he was

forced to leave Austria. Nazi-Austria was voluntarily part of a real and

murderous nightmarish regime that should never be forgotten. The fact

that I wasn’t aware of this historical figure on the 50 ATS bill

was for me shocking and is now seen by me as symptomatic for the Austrian

way to deal with its own history for many years. This brings us back to

the question “Who wants to know anyway?” Even though I have

studied quite a bit of this history and did all kind of extra “home

work” in order to find out, I still haven’t asked all the questions

possible concerning my own parents and grandparents. Do I dare to know?

Do we want Verdrängung, repression? If Paul Celan is known for saying,

“Death is a master from Germany,” I might add, “Repression

is a master from Austria” without suggesting that Austrians played

a reduced role in the 20th century’s industry of death. For this

publication, I asked Paul Mattick as well as Sylvère Lotringer

to contribute a text of their own choice. Lotringer, how leads the life

of a multi-coastal somnambulist, has written extensively on art and philosophy

and has worked with me on other publications in the past. Mattick is an

art historian and critic and has extensively published on economics, critical

theory, art and money. By accident, these two writers and friends have

their own history with Nazi-Europe. Lotringer was persecuted as a Jewish

child in Nazi-occupied France and had to hide under a fake Christian identity

with an adopted identity in a different geographic region away from his

family. Mattick’s parents were forced to flee Austria and emigrated

to the USA where he was born. None of these biographical facts played

a deciding role in the commissioning of their texts.

I want to conclude this introduction with the statement that we are always

part of a historical process and that the writing of history and histories

is political as well as part of history itself. The Austrian contribution

to the iconography of the new multinational Euro doesn’t include

any indication to its recent history. Though different national icons

are still present on Euro coins, this new European currency stands for

the departure from national currencies. The creation of a unified European

market with a unified denationalized currency seems to be the solution

to new globalized conditions where productions, (intelligent) labor, and

capital flow relatively freely. The Euro, symbolizing the results of the

ideas and the politics of the European Union, may also be seen as an answer

to centuries of national slaughtering and chauvinistic competitions. There

rests only the cardinal question of whether this new European economic

course – with not even everybody on board – will trigger the

necessary political and ideological unifications that are crucial to make

Europe a functioning entity able to withhold destructive pressures from

within as well as from outside. As a bitter reminder of the past, we should

not ignore that since the reinvigorated implementation of a unified European

zone has become a reality, reactionary political forces are regaining

momentum. Neo-nationalisms, xenophobia, racism, the structurally biased

inability and refusal of the full economic, cultural and ideological integration

of its large, mostly Muslim immigrant population and cold-blooded right

wing radicals engaging in violent actions could gain such explosive power

that again, a new kind of money could – hopefully not - become a

nightmarish reality. Over the last hundred years, Austria has changed

its currency five times – and we know why. Money echoes politics,

and so do many of my dreams.

November 2005

exhibitions at baumgarnter with dreams

some of these dreams: click